Federal Debt: High and Climbing

With rising federal debt, it’s crucial to understand its implications for the economy and government programs that impact us all.

Key Takeaways

The newly approved federal budget doesn’t reduce the government’s debt burden, which analysts project will continue growing.

Interest payments and mandatory outlays for programs like Social Security and Medicare leave little room for meaningful discretionary budget cuts.

The federal debt burden may increase borrowing costs for consumers and companies, challenge investors and jeopardize critical programs.

After years of warnings about government spending and debt, you have been tempted to tune out the latest budget debate. We get it. The budget numbers are large, and the timelines on some debt forecasts are so distant they may seem like something you don’t need to worry about today.

This article aims to provide context for recent budget negotiations, analyze factors affecting federal debt, and discuss its potential impact on you.

How We Got Here with the 2025 Federal Budget

Budget negotiations began well before President Donald Trump took office. After significant arm-twisting, the bill narrowly passed both houses of Congress, and the president signed it on July 4. It extends Trump’s 2017 tax cuts while reducing spending on services such as Medicaid and food assistance for the poor to help finance further tax cuts.1

The legislation doesn’t address the federal government's rising debt. The federal debt stands at more than $36 trillion, and the new law raises the debt ceiling by $5 trillion. The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates the budget will increase budget deficits by $3.4 trillion over the next 10 years.2

Federal Debt and Deficits: What You Need to Know

Federal Budget Surplus/Deficit

When the government spends less than it receives in revenue in a given fiscal year, it reports a surplus. Conversely, when it spends more than it collects, it reports a deficit. The primary sources of government revenue are individual and corporate taxes.

Federal (National) Debt Held by the Public

This is the total amount of money the government owes its creditors, including the American public, U.S. banks, foreign governments and investors. When the government spends more than it collects, it must borrow money by issuing Treasuries, increasing its overall debt load. Debt held by the public excludes holdings by federal agencies, most notably Social Security trust funds.

Mandatory Government Spending

This refers to ongoing spending that Congress has allocated to fund specific programs established by legislation. These programs include Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, specific income assistance programs and other transfer payments to states and local entities.

Discretionary Government Spending

This refers to the funds Congress allocates in its annual budget process to finance various government departments and agencies, including national defense.

Interest Payments

These are the government's regular interest payments to purchasers of its bonds. When the government pays interest to avoid defaulting on its debt obligations, these interest payments are a form of mandatory spending.

How Government Deficits and Debt Affect You

Economists, financial analysts and investors have long warned about the negative effects of ongoing deficits and increasing government debt. Many worry that the government’s rising debt burden limits fiscal flexibility and could trigger other knock-on effects.

Higher bond yields are among those potential impacts. Because the government spends more than it collects in tax revenue, it must issue bonds to fund its operations. If the supply of government bonds exceeds demand, bond prices fall, and yields rise to attract additional buyers. The ripple effect is significant.

For example, elevated bond yields typically lead to higher borrowing costs throughout the economy. In this scenario, you could expect to pay higher interest rates for mortgages, car loans, credit cards and other consumer debt. This dynamic also makes it more expensive for companies and entrepreneurs to obtain loans to operate and grow their businesses.

Altogether, higher borrowing costs inhibit economic growth.

Higher bond yields could also affect your investment portfolio. Initially, rising yields would hurt the value of your current bond holdings because bond prices and yields move in opposite directions. Longer term, however, the effect could be positive as higher yields increase the income potential of your interest-bearing accounts and newly issued bonds.

This could have implications for stocks. For example, if higher-quality bonds offer attractive yields, investors may demand greater return potential for taking on stock market risk. In addition, higher interest rates could weigh on corporate earnings due to increased interest expenses and borrowing costs.

You can work with your advisor to develop a diversified investment strategy for navigating such an environment.

The U.S. Has A Long History of Borrowing

The federal government has borrowed money for more than two centuries. This debt has financed efforts ranging from wars to westward expansion and space exploration.

In recent years, the government has relied on debt to cover ongoing annual budget deficits. Since 1982, the U.S. has recorded a budget surplus in only four years: from 1998 to 2001.

With spending outstripping revenue, U.S. debt tripled during the 1980s and reached $10 trillion during the global financial crisis of 2007-2009. Since then, it has more than tripled again, soaring to nearly $37 trillion.3 When adjusted for inflation, the current federal debt is 10 times greater than it was at the end of World War II.

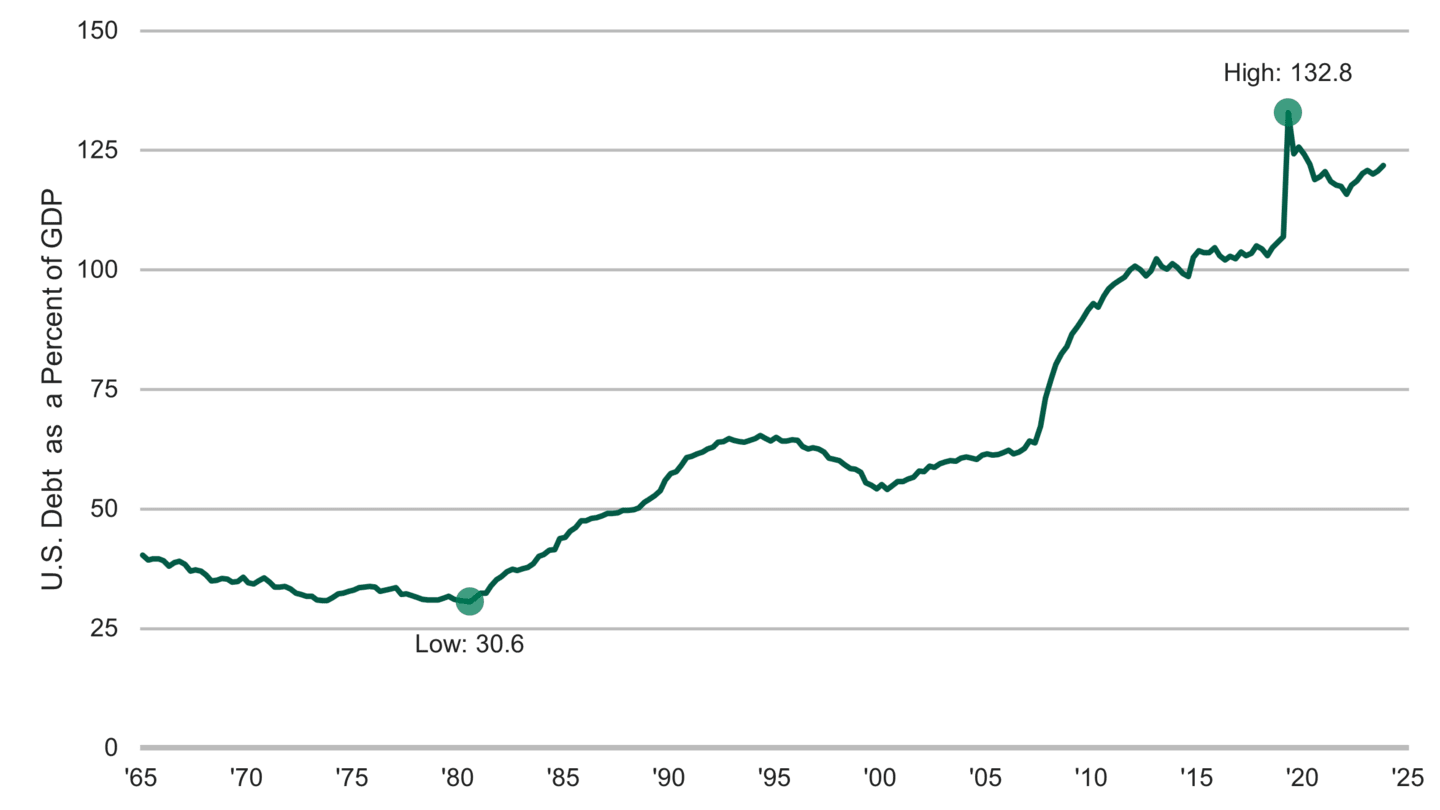

One way to put these large numbers into perspective is to look at debt as a percentage of the nation’s economic output as measured by gross domestic product (GDP). As shown in Figure 1, federal debt held by the public as a percentage of the U.S. economy has been climbing since 2001 and has hovered near 100% since April 2020.

Figure 1 | Federal Debt Held by the Public Is About the Same Size as the U.S. Economy

Data from 1/1/1965–10/1/2024. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, U.S. Office of Management and Budget.

Mandatory Spending Fuels U.S. Debt

CBO projections show mandatory federal spending on programs like Social Security and Medicare will remain the primary driver of the escalating federal debt. Furthermore, interest payments account for an increasing portion of annual government expenditures.

In 2024, mandatory spending accounted for 61% of the federal budget, with interest payments accounting for another 13%. It marked the first time the government spent more on interest payments than on funding national defense.4

The CBO forecasts that by 2035, mandatory spending and interest will consume an even larger portion of the federal budget, further limiting discretionary spending.

Given these mandatory outlays, the government's ability to reduce the budget through discretionary spending cuts is becoming increasingly limited. Even if the government eliminated all discretionary spending, it would still face a small deficit this year.

Lifting the Debt Ceiling

The U.S. debt limit represents the total amount of money Congress has authorized the government to borrow to meet its existing legal obligations. At more than $36 trillion, the national debt was nearing its ceiling before the new law raised the lid on borrowing by another $5 trillion.

The U.S. government has never defaulted on its debt, so a near-term default is highly unlikely. Congress has always raised or suspended the debt ceiling when the government reaches its borrowing limit. In fact, since 1960, Congress has extended or suspended the debt ceiling 79 times.5

Will Rising U.S. Debt Deter Investors?

Rising debt could certainly raise the government’s borrowing costs. The global bond market uses U.S. Treasuries to help set yields for other forms of debt. This could lead to higher yields across all types of debt, which may chill borrowing demand for ongoing investments.

It’s happened before. From 1985 to 1993, federal spending rose by 49%.6 Worried bond investors finally had enough. Their reluctance to invest in federal debt sent the yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note to 8% in late 1994, up from 5.4% a year earlier.7

This year, $9.2 trillion in federal debt is set to mature, nearly double the revenue the federal government collected in 2024.8 The 10-year U.S. Treasury note yield was 4.5% as of May 19, higher than the long-term average of 4.3%.9 Reissuing this debt will be more expensive than the initial cost.

There Are No Simple Answers

The budget negotiations underscored the ongoing challenges surrounding federal spending and debt. Measures, such as extending tax cuts and significantly raising the debt ceiling, illustrate the complexities of balancing fiscal policy with economic growth.

While the figures may be daunting, it's important to approach these issues with a sense of awareness that helps us grasp how they could influence the economy and, ultimately, our everyday lives. Understanding the landscape of federal budgeting can provide valuable context as we navigate the implications of these decisions, ensuring we stay informed about their potential impact on our future.

Authors

How do politics and government policies affect your money?

Kaia Hubbard and Caitlin Yilek, "Here’s What’s in Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill Passed by Congress," CBS News, July 4, 2025.

Congressional Budget Office, “Information Concerning the Budgetary Effects of H.R.1, as Passed by the Senate on July 1, 2025,” July 1, 2025.

U.S. Treasury’s Treasury Direct, “The History of the Debt,” accessed May 19, 2025; U.S. Treasury Fiscal Data, “What is the national debt?” May 16, 2025.

Benn Steil and Elisabeth Harding, “For the First Time, the U.S. Is Spending More on Debt Interest Than Defense,” Council on Foreign Relations, May 23, 2024.

U.S. Department of the Treasury, Policy Issues, “Debt Limit,” accessed May 19, 2025.

St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank, “Historical Tables, Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 1996.”

Macro Trends, “10-Year Treasury Rate - 54 Year Historical Chart,” May 15, 2025.

Aneena Alex, “$9Trillion of U.S. Debt Will Mature in 2025: Should Investors Be Worried?” Finbold, February 4, 2025.

Y Charts, “10-year Treasury Rate,” accessed May 19, 2025.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Investment returns will fluctuate and it is possible to lose money.

The opinions expressed are those of American Century Investments (or the portfolio manager) and are no guarantee of the future performance of any American Century Investments portfolio. This material has been prepared for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide, and should not be relied upon for, investment, accounting, legal or tax advice.

Generally, as interest rates rise, the value of the bonds held in the fund will decline. The opposite is true when interest rates decline.

Diversification does not assure a profit nor does it protect against loss of principal.