Climate Change, Modern Slavery and Clean Energy: The Surprising Links

Balancing environmental progress with human rights is essential in the pursuit of a sustainable future.

Key Takeaways

Fighting climate change with green tech may unintentionally exploit people most vulnerable to climate-related catastrophes.

People forced to relocate because climate change threatens or destroys their livelihoods could be forced to work for below-poverty wages or worse.

Green tech often relies on opaque supply chains that may conceal the use of child and forced labor. Reputational and legal risks are significant.

Global pressure to fight climate change is evident everywhere, from corporate board rooms and C-suites to changes in consumer preferences and new regulations. Technology is an important part of solutions to reduce the use of fossil fuels that emit greenhouse gases, with renewable energy and electric vehicles (EVs) capturing the spotlight.

However, leveraging technology to reduce carbon emissions meaningfully is happening in almost every industry, from basic industries such as mining and cement to transportation and consumer products.

Clean tech’s role in reducing carbon emissions is essential but can have adverse side effects because producing and deploying these technologies often involves abusive labor practices. As we embrace clean-tech advances, we must protect basic human rights and reduce, if not eradicate, forced labor and modern slavery from the supply chains of companies that provide us with these critical technologies.

As awareness and the demand for greater transparency increase, companies are held to higher standards. The message is clear: We must confront how to succeed in our global decarbonization efforts without exploiting the people who make that success possible.

What Do ‘Modern Slavery’ and ‘Forced Labor’ Mean?

The term modern slavery uses “modern” to emphasize that this is a contemporary issue, not something from history books. It covers debt bondage (pledging service to repay a debt), human trafficking and forced labor, each of which involves exploiting workers, often by threatening harm or other penalties, for the exploiter’s personal or commercial gain. For those working in clean tech supply chains, forced labor — both private and state-imposed — and child labor pose the largest modern slavery threats.

Modern slavery statistics from the International Labor Organization (ILO) are harrowing. In 2021, 27.6 million people were subjected to forced labor. When measured as a proportion of the population, forced labor is highest in the Middle East (5.3 per thousand people), followed by Europe and Central Asia (4.4 per thousand), the Americas and Asia Pacific (both at 3.5 per thousand), and Africa (2.9 per thousand).1, 2

Why Does Forced Labor Persist?

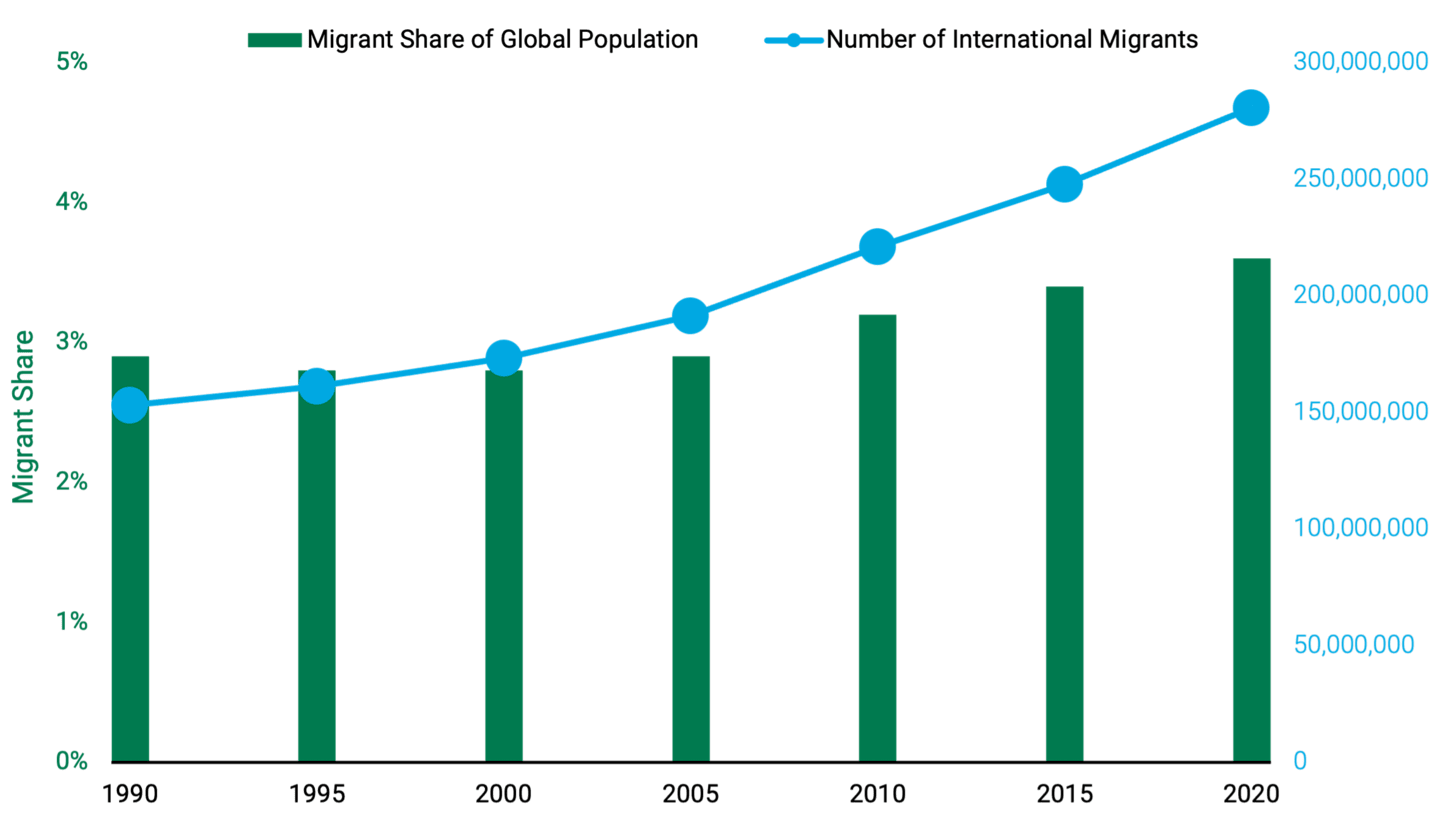

Poverty and instability are breeding grounds for forced labor because people with limited options, such as migrants and refugees, are easily exploitable. Over the last two decades, global migration has expanded nominally and as a share of the worldwide population, as shown in Figure 1.

Forced labor has risen along with increased migration, driven partly by a growing risk of “unfair or unethical recruitment policies or irregular or poorly governed migration.”3 The ILO reports that adult migrant workers are over three times more likely to face forced labor than non-migrants.4

Figure 1 | The Number of Migrants, a Group Susceptible to Forced Labor, Is Increasing

Data from 1/1/1990 – 12/31/2020. Source: Migration Policy Institute tabulation of data from the U.N. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, International Migrant Stock 2020: Destination, Table 1: International Migrant Stock at Mid-Year by Sex and by Region, Country or Area of Destination, Table 3: International Migrant Stock as a Percentage of the Total Population, Both Sexes Combined, 1990-2020. Data before 1990 is no longer available online.

A country’s coping capacity refers to its ability to prepare for and mitigate disasters and its emergency response and recovery capabilities. This includes organized activities and efforts from the government and existing infrastructure that help reduce disaster risk. In countries whose coping capacity is low, people are vulnerable to exploitation.

In regions where disruptive, often violent, political conflicts or inadequate education prevail, employers exploit workers. In such areas, school attendance is low, the rule of law is weak, and the government appears unwilling or unable to address these issues.5 Slavery thrives where a weak rule of law meets discrimination and poverty.6

The pursuit of profits motivates much of this abuse. The ILO estimates that $150 billion in private sector profits are attributable to forced labor. That’s a powerful incentive for those who pursue financial gains more than anything else and businesses that stay afloat by exploiting vulnerable workers.

The Link Between Forced Labor and Climate Change

Climate change tends to disproportionately affect the vulnerable, who are inherently at risk for abusive labor practices. People whose livelihoods are threatened by severe droughts or floods caused by climate change are highly susceptible to exploitation.

These and other climate change-related natural disasters are forcing many people to relocate, particularly in emerging and frontier markets with low coping capacity and resilience.7 The international human rights group Walk Free estimates climate-related disasters displaced 24 million people in 2021, and the World Bank predicts climate change will force 200 million people to migrate by 2050.8 The number of people involved in forced labor is likely to rise proportionately.

In addition, many of the industries that are significant sources of greenhouse gas emissions, such as mining and agriculture, are known to use forced labor, creating a cycle of victimization. Climate change and forced labor are intertwined, reinforcing the importance of pursuing a just transition to a sustainable, clean energy future. We can’t address one global problem at the expense of another.

The Connection Between Clean Tech and Forced Labor

The relationship between climate change, forced migration and forced labor extends to growth in clean tech. The United Nations reports that low-cost electricity from renewable sources could supply 65% of the world’s electricity needs by 2030 and decarbonize 90% of the power sector by 2050, thereby “massively cutting carbon emissions and helping to mitigate climate change.”9 That’s good news.

Moving away from using fossil fuels for transportation is essential to fighting climate change. Transportation produces roughly one-fifth of global emissions, with cars and trucks contributing about three-fourths.

The International Energy Agency estimates global transportation needs will double by 2070, which means more carbon emissions unless there is a massive shift to electric vehicles.10 EV skeptics point out that the electricity used to charge EV batteries may come from coal- or gas-fired power plants. However, even after considering this, EVs produce less than half the greenhouse gas emissions than traditional vehicles.11

These clean energy-clean tech solutions are essential to fighting climate change. Still, there’s a dark side: Generating solar, wind, and geothermal power and manufacturing batteries for EVs can increase forced labor.

Clean Tech Materials and Worker Exploitation: The Core of the Problem

A greener future will be more mineral-intensive because many low-carbon technologies involve greater use of metals and minerals than fossil fuel-based power and transportation.12 As a result, the vast and complex supply chains needed to produce EVs, solar panels and wind turbines are fraught with human rights violations.

Many of these clean tech solutions use raw materials that are mined, and the mining industry is notorious for exploiting workers and using child labor, particularly in emerging and frontier markets.

EV batteries rely heavily on minerals sourced primarily from the Democratic Republic of the Congo – the DRC (cobalt), China (graphite) and Indonesia (nickel).13 Cobalt mining in the DRC is particularly well-known for using child workers and exploitative labor practices.

The nation suffers from many of the underlying factors giving rise to forced labor and modern slavery — political instability, poverty and violence. In addition to exposure to toxic substances, workers in Congolese cobalt mines typically face dangerous working conditions with inadequate protective equipment and safety measures.

Child labor is perhaps the most heinous aspect of the DRC’s cobalt operations. Poverty has given rise to artisanal, small-scale mines (ASMs) run by individuals or small groups rarely associated with large mining companies. These informal operations are known for putting children to work in dangerous settings.

The inhumane conditions associated with mining cobalt in the DRC, which is essential to clean-tech, are well-documented. (See, for example, How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives by Siddharth Kara).

Sources report that children as young as 6 are involved in mining and quarrying, one of the worst forms of child labor. These children often suffer from neurological damage, musculoskeletal disorders, sexual abuse and injuries from beatings.14

Estimated at 200,000, the number of ASMs in the DRC has grown along with the demand for cobalt, which surged by 22% in 2021 and is forecast to increase by around 13% annually for the next five years.15 Some companies, including Microsoft, are exploring the possibility of formalizing artisanal mines to address abusive labor practices, but this will take the right coalition partners and enormous funding. For now, increasing the use of recycled materials is a more reliable way to reduce the mining industry’s human rights violations and environmental damage.

Apple has suffered from negative publicity related to its supply chain labor practices and announced in April 2023 that it seeks to use 100% recycled cobalt in all Apple-designed batteries by 2025.16 The company’s efforts to use climate-friendlier approaches to its technologies, including innovative new R&D for end-of-product-life disassembly and recycling, can reduce environmental harm and labor exploitation. Apple’s global influence can inspire others to make similar changes.

Demand for Graphite, Nickel and Wind Turbines Leads to Human Rights Violations

Allegations of human rights violations in China impact many global supply chains. While most reports focus on state-sanctioned exploitation of the (predominantly Muslim) Uyghur population in the factories of China’s Xinjiang region, there is also evidence of forced labor in graphite mining and refining.17

These negative impacts have spread with China’s increased investment in nickel smelters in Indonesia to capitalize on surging demand for EV batteries — over 75% of EV batteries are currently produced in China.18 The January 2023 deaths of two employees of a China-owned nickel mining operation in Sulawesi highlight increased violence associated with Indonesia’s nickel mining boom, and allegations of poor working conditions, safety lapses and unfair pay have sparked deadly protests.19

Mining isn’t the only source of labor exploitation in producing clean tech. Wind turbines require balsa wood, 75% of which comes from Ecuador. Demand for balsa began to escalate in 2019 when the U.S. and China scrambled to meet wind turbine tax credit and subsidy deadlines; a lack of regulation led to human rights violations and labor exploitation in the industry.20

This is a prime example of how poverty increases susceptibility. Loggers employed local indigenous people living in prime harvesting areas, and while some were eager to reap the benefits of their land, many were never paid. Those who were paid often received payment in the form of liquor or marijuana, fueling already rampant substance abuse and violence.21 Unsafe working conditions made the situation even worse.

Although metal blades are replacing balsa, modern slavery in wind turbine production persists because the turbines require large amounts of copper. For example, a single 3-megawatt wind turbine contains about 4.7 tons of copper.22

Copper mining often relies on migrants trapped in exploitative situations through debt bondage. Children in impoverished areas where copper is mined forgo school to dig, haul and process copper ore to earn money for their families. This work harms their physical and mental health.

Forced Labor in Production and Manufacturing

Human rights violations are found in solar energy supply chains, often linked to China. In November 2022, the Clean Energy Council reported that 40%-45% of global solar-grade polysilicon, a central component of solar panels, comes from production linked to China’s Xinjiang region.23

The exploitation of the Uyghur population continues to garner global attention, with reports indicating factory workers in the Xinjiang region face extreme human rights abuses; some even allege genocide.

An estimated 1.8 million Uyghurs have been detained in what the Chinese government calls reeducation camps, where they are taught to embrace Chinese culture in place of their own religious and ideological beliefs. They are then forced to work in factories under a government-led labor transfer program, living in conditions that have been described as “inhuman.”24

International Forced Labor Affects U.S. Auto Makers

In December 2022, the Wall Street Journal published an exclusive article titled “Tesla, GM Among Car Makers Facing Senate Inquiry Into Possible Links to Uyghur Forced Labor.”25 The authors highlight the automakers’ often unrecognized involvement in human rights violations in their supply chains. From the day the article was published to the close of the market the following day, Tesla’s and GM’s stock prices dropped 9.45% and 3.81%, respectively. By comparison, the S&P 500® Index fell by 0.22%. These losses represented a two-day decline in market value of $45.5 billion for Tesla and $2.9 billion for GM.

The U.S. Senate expanded an investigation into the issue at the end of March 2023, stating that counting on tier 1 suppliers (those that sell directly to a company) to oversee their suppliers and so on down the supply chain isn’t sufficient for ending modern slavery and forced labor.

Investors are taking note. GM and Tesla are facing legal scrutiny, headline risks associated with forced labor in supply chains are affecting stock prices, and compliance costs to expand companies’ due diligence processes along the value chain are rising.

Costs and Benefits of Policies Against Modern Slavery

Regulations forbidding forced labor are essential to discourage the practice but can increase costs when supply chains are disrupted. For example, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agency has confiscated solar panels made in China (which has a near-monopoly on solar panel manufacturing globally) under the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act. The law prohibits the U.S. from importing products from the Xinjiang region.26

From June 2022 through October 2022, the CBP detained 1,000 shipments of solar energy components.27 As a result, solar panel installations in the U.S. fell by 23% in the third quarter of 2022, over 20 gigawatts of solar projects were delayed, and the cost of some solar modules rose 30%-40%.28

Despite these costs, research shows that companies that recognize and address human rights risks are strongly associated with better financial performance, supply chain resilience, and operational stability. Robust due diligence can help guard against costly litigation, employee turnover, and loss of consumers’ trust, clearly benefitting shareholders. From an economic perspective, taking a stand against modern slavery and forced labor improves a company’s sustainability.

American Century's Stance on Modern Slavery

Our Modern Slavery Investment Statement affirms that:

“We intend to avoid conducting business with or supporting any organization involved in the categories of serious exploitation as provided for in current modern slavery legislation.”

We seek to identify and manage risks related to human rights and modern slavery in our investee companies based on our sustainability research framework and aligned with our fiduciary duty. For example, if we determined that a company had inadequate or opaque risk management practices in this area or had ongoing or historical practices that raised concerns based on verifiable data, we would initiate a formal engagement protocol.

We are also an original member of Investors Against Slavery and Trafficking Asia-Pacific (IAST APAC), a coalition dedicated to fighting modern slavery through investing. IAST APAC pressures companies in the APAC region to find, fix and prevent modern slavery, labor exploitation and human trafficking in their value chains.

Navigating the Interconnected Challenges of Clean Technology

The world can only achieve critical carbon dioxide-reduction targets by greatly increasing the use of green energy, electric vehicles and many other clean technologies that depend on complex and often opaque global supply chains.

Modern slavery and the use of forced labor in producing these technologies are becoming more apparent as companies, investors and consumers demand greater supply chain transparency.

There’s a clear connection between environmental goals and social issues. Companies that ignore these concerns risk negative media coverage, customer backlash, legal sanctions and fines. Tackling climate change using clean energy and new technologies is essential to a sustainable global economy, but modern slavery can’t be tolerated as a “cost” of a greener future.

Authors

Head of Sustainable Investing

Sustainability: It’s in Our Genes®

Sustainability isn't just something we practice; it is part of who we are as a company and as global citizens.

International Labor Organization, Walk Free, and International Organization for Migration, “Global Estimates of Modern Slavery: Forced Labor and Forced Marriage,” September 2022.

Stephen Hall, “Modern Slavery Is Increasing — 1 in Every 150 People Are Victims,” World Economic Forum, September 16, 2022.

Hall, “Modern Slavery Is Increasing,” September 16, 2022.

International Labor Organization, Walk Free, and International Organization for Migration, “Global Estimates of Modern Slavery,” September 2022.

International Labor Organization, “Profits and Poverty: The Economics of Forced Labor,” 2014.

Jasmine O’Connor, “Climate Change and Modern Slavery: The Nexus That Cannot Be Ignored,” June 8, 2022.

International Labor Organization, Walk Free, and International Organization for Migration, “Global Estimates of Modern Slavery,” September 2022.

Clement, Rigaud, and de Sherbinin, et al., “Groundswell Part 2: Acting on Internal Climate Migration,” September 9, 2021.

United Nations, “Climate Action: Renewable Energy – Powering a Safer Future,” accessed December 15, 2023.

International Energy Agency, “Energy Technology Perspectives 2020,” revised February 2021.

International Energy Agency, “The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions,” May 2021.

Kirsten Hund, Daniele La Porta, and Thao P. Fabregas, et al., “Minerals for Climate Action: The Mineral Intensity of the Clean Energy Transition,” World Bank, 2020.

Andrew Mollica, Adrienne Tong and Stephanie Aaronson, “U.S. Car Makers’ EV Plans Hinge on Made-in-America Batteries,” Wall Street Journal, February 6, 2023.

Child Labor Forum, “Child Labor in Mining and Global Supply Chains,” May 2019.

Andy Home, “Is It Time to Embrace Congo’s Artisanal Cobalt Miners?” Reuters, April 4, 2023.

Apple is also seeking to use 100% recycled rare earth elements in its magnets, and 100% recycled materials in soldering and recycled gold plating for Apple-designed printed circuit boards.

Ana Swanson and Chris Buckley, “Red Flags for Forced Labor Found in China’s Car Battery Supply Chain,” November 4, 2022.

Mollica, Tong and Aaronson, Wall Street Journal, February 6, 2023.

Jon Emont and Austin Ramzy, “Chinese and Local Workers Clash at Indonesia Nickel Smelter, Leaving Two Dead,” Wall Street Journal, January 16, 2023.

The Economist, “The Wind-Power Boom Set Off a Scramble for Balsa Wood in Ecuador,” January 30, 2021.

The Economist, “The Wind-Power Boom Set Off a Scramble for Balsa Wood in Ecuador,” January 30, 2021.

Neil Hume and Henry Sanderson, “Clean energy is driving a copper supercycle,” Australian Financial Review Magazine, June 9, 2021.

Clean Energy Council and Norton Rose Fulbright – Australia, “Addressing Modern Slavery in the Clean Energy Sector,” November 2022.

Adile Ablet, Short Hoshur, and Bahram Sintash “China Says Its Camps Are Closed, but Uyghurs Remain Under Threat,” Radio September 17, 2023.

Yuka Hayashi, “Tesla, GM Among Car Makers Facing Senate Inquiry Into Possible Links to Uyghur Forced Labor,” Wall Street Journal, December 22, 2023.

Alan Neuhauser, “U.S. Crackdown on Chinese Forced Labor Hits Solar Industry,” Axios, January 13, 2023.

Nichola Groom, “U.S. Blocks More Than 1,000 Solar Shipments Over Chinese Slave Labor Concerns,” Reuters, November 11, 2022.

Neuhauser, “U.S. Crackdown on Chinese Forced Labor Hits Solar Industry,” Axios, January 13, 2023.

Sustainability focuses on meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs. There are many different approaches to Sustainability, with motives varying from positive societal impact, to wanting to achieve competitive financial results, or both. Methods of sustainable investing include active share ownership, integration of ESG factors, thematic investing, impact investing and exclusion among others.

The opinions expressed are those of American Century Investments (or the portfolio manager) and are no guarantee of the future performance of any American Century Investments portfolio. This material has been prepared for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide, and should not be relied upon for, investment, accounting, legal or tax advice.

References to specific securities are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended as recommendations to purchase or sell securities. Opinions and estimates offered constitute our judgment and, along with other portfolio data, are subject to change without notice.