Mind the (Spending) Gap: What Does It Mean for Markets?

The pandemic scrambled the relationship between personal income and spending. The path to closing that relationship gap is likely to be painful—particularly for stocks.

Key Takeaways

COVID-19 stimulus and pent-up demand from lockdowns upset the historical relationship between personal income and spending.

Post-COVID, consumers demanded more than the economy could produce, contributing to higher inflation.

Closing the spending-income gap could affect economic growth or corporate earnings—both of which could pressure stocks.

Personal consumption and income are closely related. That checks out with our economic intuition: For most people, higher wages will translate to higher spending.

The Historical Relationship Between Spending and Income

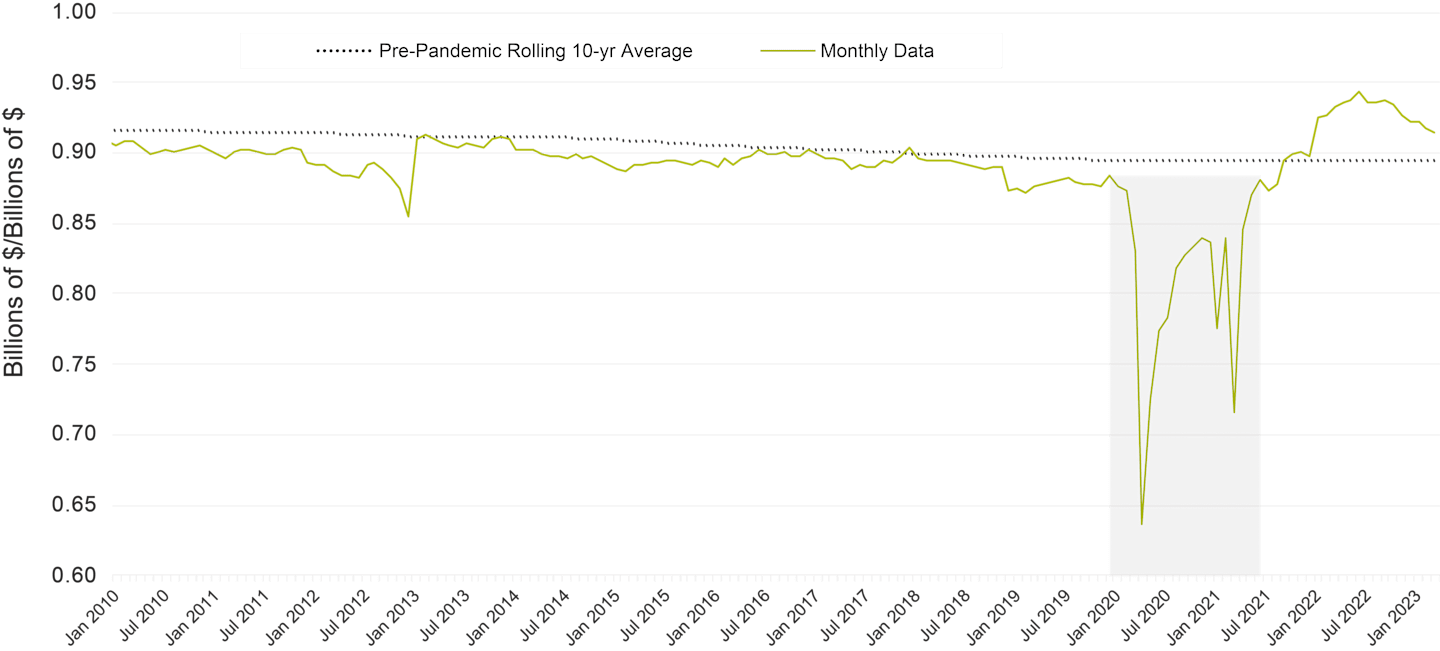

Historical data also show that spending and income moved in lockstep until 2020, when the pandemic ripped them apart. That’s because COVID-19 lockdowns drastically reduced consumption, while government programs and stimulus contributed to increased pay.

Personal spending relative to income has been relatively stable over time. The graphic below shows just how dramatically that relationship was upset during the pandemic.

Spending as a Percentage of Income

Personal Consumption Divided by Disposable Personal Income

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) and U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Data from 1/1/2010 - 3/31/2023.

The gap left consumers with excess savings and a strong desire to spend. So, it makes sense that once the economy reopened, consumers wanted (and could afford) even more than the economy could produce. That is a direct cause of the recent 40-year high in inflation.

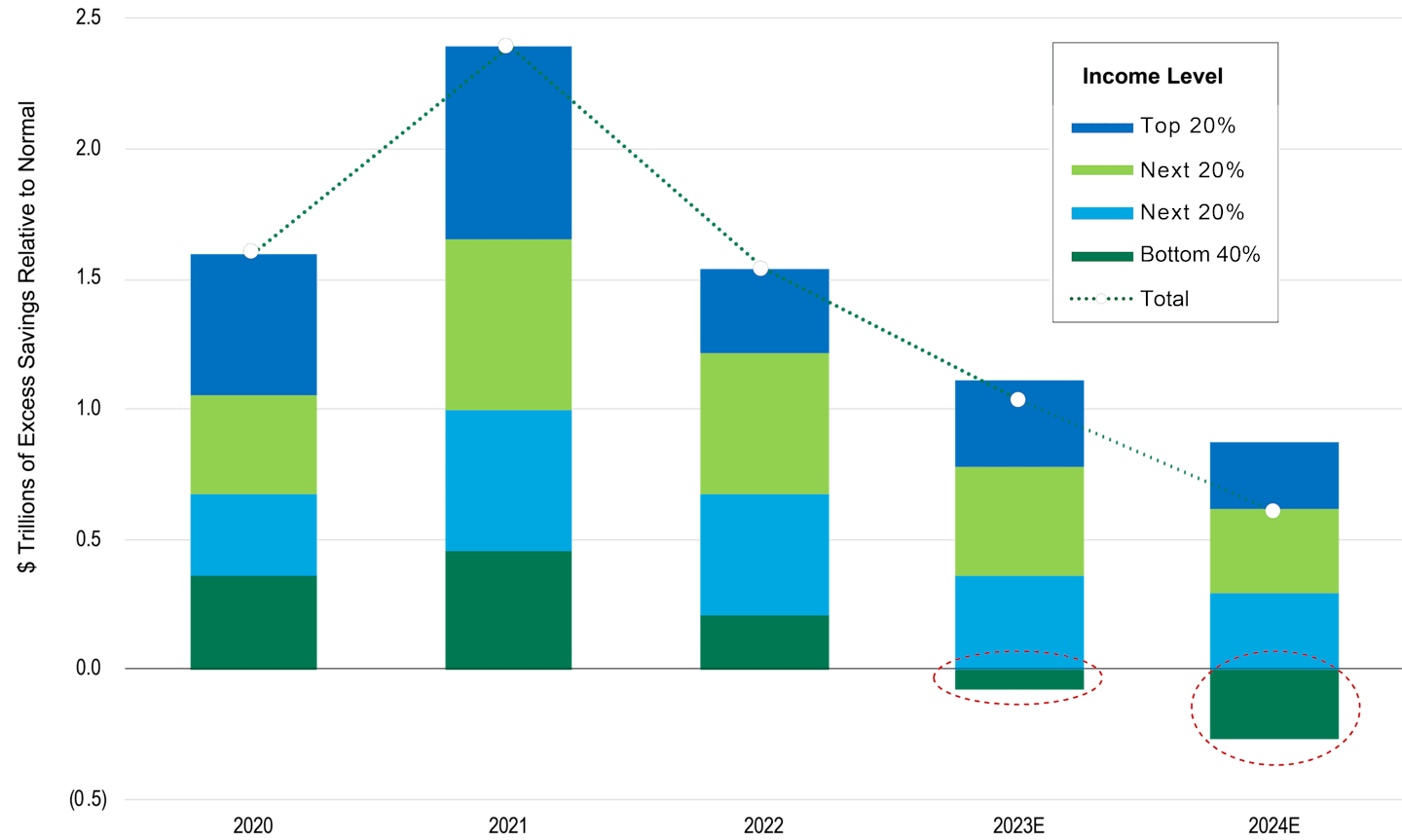

You can see these effects in the excess savings data below. The surge in savings peaked in the wake of the pandemic and has been coming down ever since.

Excess Savings by Income Level

Excess Savings/Deficit Relative to Normal Levels*

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Rubinson Research estimates. Data as of 12/31/2022.

*Normal uses the average savings level for 2015-2019 for each income group. For groups with positive savings rates, we grow savings by 5% for each year. For groups with negative savings rates, we hold the level steady so as not to compound a negative.

Consumption has been so strong in the post-lockdown era that it has outpaced income—and in the process soaked up roughly $1 trillion of excess pandemic-era savings. Consumers were able to increase purchases even in the face of rapidly rising inflation by using their excess savings. Estimates also suggest that lower-income consumers will use credit cards and other forms of debt to finance spending going forward (negative saving).

As a result, the situation is now reversed from what it was during the pandemic. The huge increase in post-lockdown consumption closed the gap with income and then some, overshooting its historical level of about 89% of income.1

If history is any indication, this gap could close in the short term—as soon as consumers run out of extra savings.

Rapid Return to Normal Could Spell Trouble for Stocks

One way to close the spending-income gap is for income to increase faster than consumption. If that were to happen, higher wages would argue for lower profit margins for companies going forward. Conversely, if spending were to fall to meet income, then less consumer demand would argue for slowing economic growth and/or declining inflation.

Unfortunately, none of the scenarios are particularly desirable for stocks. Let’s look again at our Spending as a Percentage of Income chart. It shows that consumption would have to fall by about 2% to get back in line with the historical norm since the global financial crisis. The catch is that a drop in spending of that size could trigger a recession.

The adjustment could be even more painful if we return to the relationship between spending and income that held in 2018-192, the years just prior to the pandemic. That would imply a 5% decrease.

On the other hand, if real income (income minus inflation) were to increase, it means that wage growth would have to outpace inflation. Wages running ahead of inflation and economic growth would pressure corporate profit margins.

Both alternatives bode poorly for stocks, as the above-mentioned scenario of lower consumption growth would pressure revenues. Either outcome would reduce real corporate earnings growth, leaving stocks in a vulnerable spot through this economic adjustment.

However it plays out, this relationship bears watching because it has such profound implications for the economy and markets.

Authors

Senior Portfolio Manager and Head of Multi-Asset Research

Stay on Top of Market Trends

Get the latest insights from our investment teams.

Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) and U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Data from 7/1/1960 - 3/31/2023.

Bureau of Economic Analysis, Rubinson Research estimates. Data as of 12/31/2022.

Investment return and principal value of security investments will fluctuate. The value at the time of redemption may be more or less than the original cost. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

The opinions expressed are those of American Century Investments (or the portfolio manager) and are no guarantee of the future performance of any American Century Investments portfolio. This material has been prepared for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide, and should not be relied upon for, investment, accounting, legal or tax advice.